In the old days, training “specifically” for climbing was almost unheard of. You either just climbed or you were one of the few climbers who trained in the weight room and did some door jamb pull-ups. Over the years, things changed. As climbs got hard and more physically challenging we sought out ways to beat the pump, many of which derived from the tricks of old time strongmen and gymnasts.

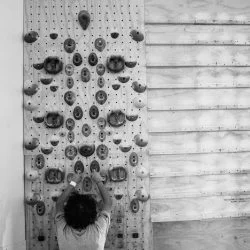

Exercises such as dumbbell work, rope climbing, and even nail bending found their way into climbers’ routines. In the 1980s, climbing-specific training devices began to hit the market. The Metolius Simulator, various grip devices, and even rudimentary climbing walls appeared all over Europe and North America. By the end of the 1990s, we were all training on steep walls covered in plastic holds – converting our training into almost a perfect mimic of the sport.

Knowing the value of specificity in training, defined as patterning training after the movement and metabolic demand, many of us plunged full-on into “climbing to climb” as our sole form of training. Although this is a general rule that represents a good step forward in the sport, I think we may have stepped too far. There are a few reasons that non-specific movements should still be used by climbers:

- Too much strength and conditioning that mimics the sport increases risk for overuse injuries. If we only train the forearms by gripping small edges in a static position, we lose all the benefits of flexing, extending, and rotating the wrist. These benefits include decreased elbow strain, increased blood flow, and a general increase in strength.

- Too much work strengthening one group of muscles can cause an imbalance if the antagonists are not trained. We see frequent shoulder and elbow injuries in climbers who get really good at pulling, but neglect the pushing/extending antagonists. This problem can affect any joint in the body, but climbers primarily see these problems in the joints of the arm – shoulders, elbows, and wrists.

- On the same token, we frequently see climbers’ finger strength and pulling strength level-out in what’s called a “hard plateau,” where no amount of focused strength training can increase force production. This is more often than not due to an under-strong antagonist. If there is a large imbalance in muscle strength around a given joint, the nervous system will effectively hold back the strong muscle to prevent injury or bad movement. For example, simply strengthening the extensors of the forearm can be enough to jump start your grip strength again.

I’m not going to tell you to stop your specific training, but I suggest adding some of the following exercises to your climbing strength plan. By doing flexion and extension at the wrist, finger extensions, and doing some “crushing” movements, you’ll increase your general hand strength and might see some nagging problems drop away.

Wrist Curls

The wrist curl is the most basic forearm flexion exercise. With the forearm supinated and a dumbbell in the hand, work from full extension (wrist open) to full flexion (wrist closed). Move slowly and in control for 8 to 10 repetitions. Begin each set with your “strong” hand, and follow it with the “stronger” hand.

If you are moving 50 or more pounds in these sets, you could experience wrist pain. In such a case, consider switching to the Heavy Finger Roll, which can best be done with a barbell in a power rack. For this exercise, you’d roll the bar down to the tips of the fingers, then back up to full flexion. Although not technically wrist flexion, it serves our purpose of training the muscles through a full range of motion.

Reverse Wrist Curls

This time you’ll place your forearm on the bench in a pronated (palm down) position. Holding a lighter dumbbell than you used in the Wrist Curl, work from a fully flexed to a fully extended position. Understand that you’ll still be working the flexors to hold on to the dumbbell, so give yourself plenty of rest if you are combining this with other grip exercises. Use the same 8 to 10 rep rule here.

Crushing

Those little donuts are nice for warming up, but they won’t do the trick to make you stronger. For crushing to be effective, you’ll need to train with progressively harder resistances. A few companies make spring-loaded grippers, the best for climbers are the Captains Of Crush Grippers from Iron Mind. Select a resistance that you can close (touching the handles at the end of each rep) for 5 to 10 reps. Alternating hands, perform as many clean reps as you can in each set. Once you can do 5 sets of 10 reps, reward yourself by buying the next harder gripper.

Finger Extensions

There are a few good elastic extension devices on the market, but the best bang for your buck is going to be a 1cm rubber band. Placing all the fingers and the thumb inside the band, extend outward to a full spread of the fingers. If you can do more than 10 reps, add a second band or get a thicker one. Occasionally, climbers will complain about this exercise straining their little finger. These climbers clearly need stronger pinkies! Although cheap or free bands are widely available in the grocery store, you can buy a nice set of progressive bands, also from Iron Mind.

Wrist Rotation

You need a small sledge hammer, probably in the 3 to 6 pound range. With the elbow held tight to your side, rotate internally until the handle of the hammer is parallel to the floor. Return to the top, then rotate externally until you reach parallel. On my hammer, I have wrapped tape around the handle every few inches so that I can change how close to the head I place my hand, and can thus adjust resistance. 5 reps each direction is the proper number. Of all the listed exercises, I caution you to be conservative in your progress in this one. This exercise is unlike any climbing exercise you’ve ever done, and too-rapid an increase in load can cause undue elbow pain.

The exercises above should be done 2 or 3 times per week and can be inserted into almost any other workout. By embracing some non-climbing grip strength training, you’ll guard against injury and you’ll see your finger strength start going up again. Remember, it took you a long time to build the imbalance, so be patient in pushing things back the other way.

A second good option is to pick just one exercise per month and work it into every training session. Twice per year, you could then insert a general grip phase (ideally along with a big strength focus) and really see the strength of your lower arm improve.

—

We’ve been experimenting with substituting some of the non-specific work above with a normal hangboard routine. Although our highly unscientific research is still being tested, the general gist is this: Instead of doing 4 positions on the hangboard for 3 sets of 8 seconds each, we back off to 2 positions on the hangboard for 3x8sec and add in Heavy Finger Rolls for 3×8 and Reverse Wrist Curls for 3×8 on each side.

The athletes that have completed this protocol for a full 12 sessions are testing out with similar gains to the ones doing strictly edge hangs. This begs the question “how much pure hangboarding do you need to do?” It follows that doing some non-specific work may help reduce the risk of overuse injuries in the fingers, and may have other benefits as well.

Tags: Finger Strength, finger training, Grip Strength, grip training

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hello, I am a computer scientist and I have been. Loosing strength in my hands lately. I need to develop grip strength for my key board movement. I really enjoyed this article. Thank you. I never new how important hands can be until reading this article.